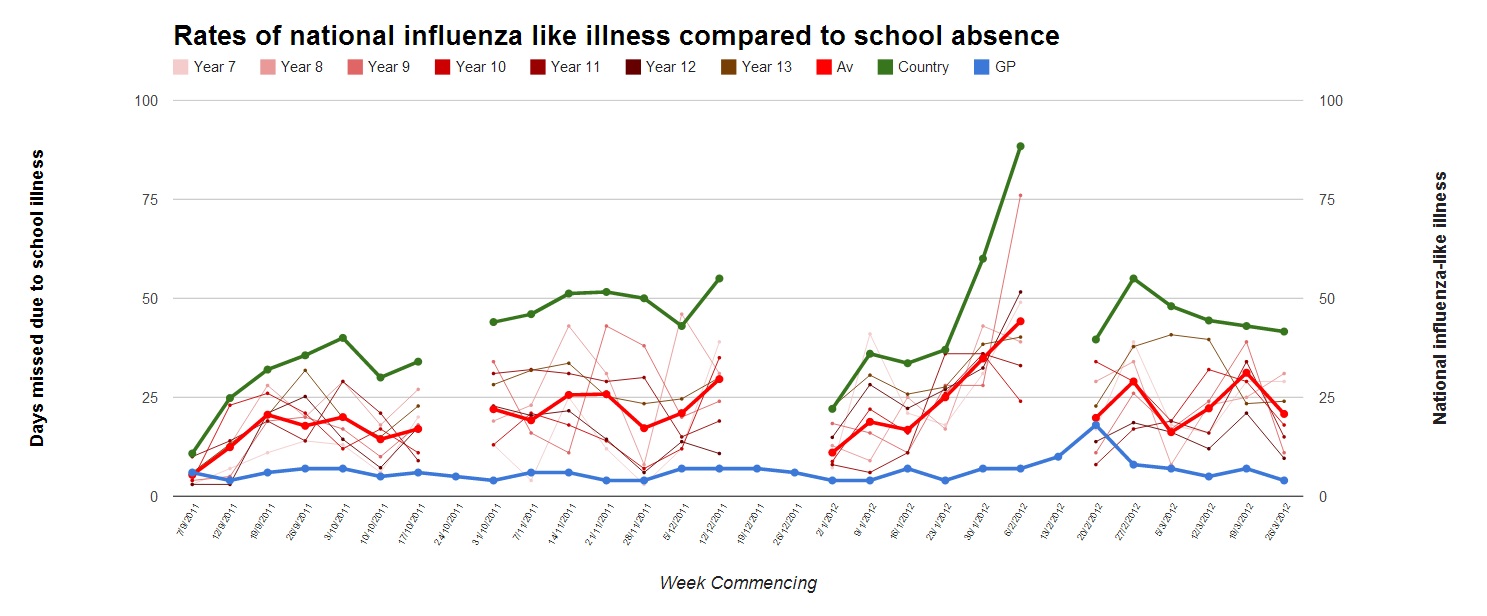

We performed a time-trend analysis to compare absence-due-to-illness levels in our school against influenza-like illness data reported by the Royal College of General Practitioners. Overall our school appeared to have lower-than-average absence-due-to-illness levels however there was a surge in absence levels alongside a surge in the national data shortly before the peak in influenza-like illness.

Background: Our school is of an average size for a secondary school in the UK and is based in the south of the country on the edge of a large town. The intake is reasonably affluent. People are prepared to travel some distance to come here, up to 45 miles, and many come on buses.

Observations: The national data seemed to settle into a background level of between 30 and 55 illness sessions per week. The times that broke from this pattern happened just after long (greater than one week) breaks and just before the February half term. It’s likely that in the time immediately after holidays, people are better rested and less prone to getting ill. We searched for information linking fatigue to the body’s immune response but were unable to find any evidence we could access to confirm if there was a link. Psycholological factors will also play a part here. Many parents and students will be keen to make a good start to a new term and they may be more likely to come into school even if they are ill. Absence levels seemed to peak just before the holidays in all cases. The opposite factor may be coming into play with parents more likely to let their children stay at home thinking that the time they are missing will be less important. There was a particularly big jump just before Christmas.

There appeared to be a peak in illness in our class in the middle of the second half of the Autumn term and this also appeared in the year-wide data but this did not affect the whole-school data. Looking at the year group data at this point, there was a lot more variance than there was in the first term. So although it seemed like more people were off, they were just the people that we were more aware of. There was much less variance seen in the school-wide data and the national data was even smoother as were were effectively averaging results over a much larger sample.

The most interesting thing to notice was the peak in absence levels shortly before half term in February. Many people were off and were reporting flu-like symptoms before they left and after they came back. Lots of staff seemed to be off at the time as well but we have no evidence for this apart from remembering being in a lot of lessons with cover teachers! The national flu peak in the GP data came just after this. Unfortunately we had no data for the week before the national peak and the national peak itself wasn’t very big compared to the background levels so it’s unclear how significant it is that the school and national school data all peaked just before the national GP data.

Our school data seemed on average, lower than the national data. It’s possible that the children at our affluent school, are better nourished or keep stricter sleep routines than children in other schools which could make our absence levels lower if the people at our school are better-prepared to fight an illness.

It was interesting to note that the Y13 data broke away from the rest of the school data in the early weeks of January around the time they were sitting exams. This could either be because they wanted extra study leave or it could be that they were more prone to getting ill in a period of stress. We should ensure that this anomalous pattern does not influence the school data by removing it from our averages. Year 9 seemed to be very badly affected by the illness in the run up to the February half term – we’re considering doing a survey of the year group to try to find out why they were so badly hit.